.png)

TL;DR: As you get more senior, there's pressure to stop doing hands-on work and focus on "strategy." I think that's a mistake. As a Principal PM, I spend several hours each week building AI automations in n8n—not because I have to, but because it makes me better at my actual job. The repetitive cognitive work that doesn't need my judgment but still requires my context—status reports, research synthesis, content reformatting—can be automated, freeing my limited product-thinking time for actual product thinking. The PMs who will struggle in the next few years aren't the ones who can't code. They're the ones who wait for someone else to build their productivity systems.

Why Do Senior PMs Stop Doing Hands-On Work?

There's an unspoken expectation in most organizations that as you get promoted, you transition from "doing" to "directing." You set strategy, delegate execution, review output, and attend meetings. The hands-on work becomes someone else's job.

This model made sense in a world where leverage came from coordinating human work. If your main tool for getting things done was other people, then your job at senior levels was optimizing how those people worked.

But that world is changing.

What's the expectation as you get promoted?

The typical career progression for PMs looks like this:

- Associate/Junior PM: You do the work. Research, specs, analysis, coordination.

- PM/Senior PM: You do some work and delegate some work. More meetings, less building.

- Lead/Principal PM: You direct work. Strategy, stakeholder management, team leadership.

- Director/VP: You direct the people who direct the work. Almost no hands-on anything.

Each promotion means less doing and more managing. This is presented as growth—you're now working "on" the product instead of "in" it.

Why is that expectation often wrong?

The problem with this model is that it assumes the work that needs doing is constant, and the only question is who does it. But the nature of work changes when you have AI tools that can handle significant portions of cognitive labor.

A senior PM in 2020 who stopped writing specs because they had junior PMs to do that was making a reasonable tradeoff. A senior PM in 2025 who isn't using AI to accelerate their own spec-writing is just being inefficient.

The leverage has shifted. It's no longer just "coordinate humans" vs. "do it yourself." It's "coordinate humans" vs. "do it yourself with AI assistance" vs. "automate it entirely."

Staying hands-on doesn't mean doing junior work. It means using tools that multiply your individual impact beyond what delegation alone can achieve.

What's the Real PM Productivity Bottleneck?

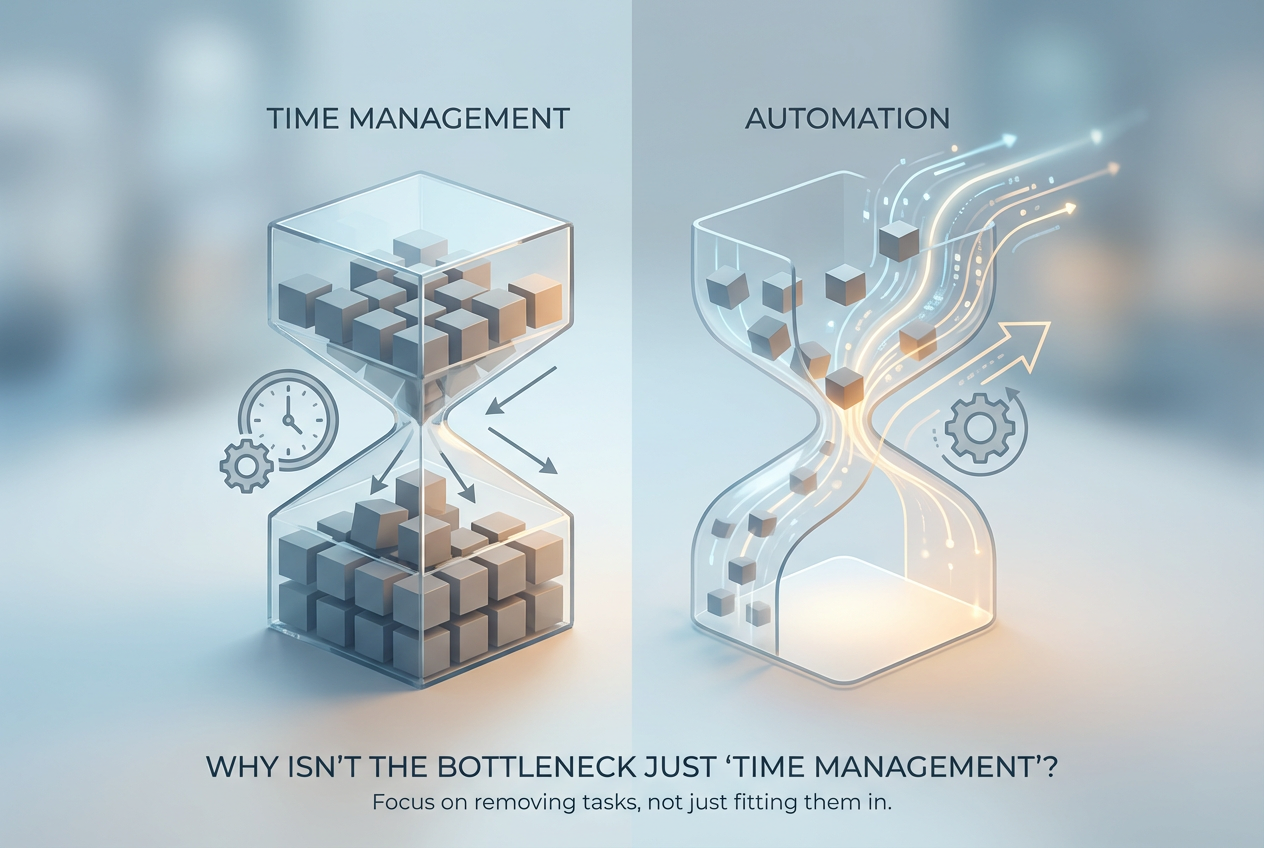

Most PM productivity advice focuses on time management: block your calendar, batch your meetings, say no more often. That advice isn't wrong, but it misses the deeper problem.

The bottleneck for most PMs isn't calendar management. It's the repetitive cognitive work that doesn't need their judgment but still requires their context.

Why isn't the bottleneck just "time management"?

Time management assumes your tasks are mostly valuable and the question is fitting them in efficiently. But when you audit where PM time actually goes, a significant chunk is work that:

- Follows predictable patterns (weekly status updates, research queries, report formatting)

- Requires your context to do correctly (can't easily hand off to someone unfamiliar)

- Doesn't benefit from your unique judgment (the output would be the same regardless of seniority)

- Repeats frequently (same structure, different inputs each time)

This work isn't hard. It's just slow. And it crowds out the work that actually needs your product thinking.

Time management helps you fit more tasks into your day. Automation removes tasks from your day entirely.

What kind of work is actually worth automating?

The best automation candidates share these characteristics:

Repetitive with consistent structure. Same format, same steps, same logic—just different inputs each time. Weekly reports, research synthesis, data pulls.

Context-dependent but not judgment-dependent. You need to do it because you have the context (you know what metrics matter, what competitors to watch, what stakeholders need). But the actual execution is mechanical.

Time-consuming relative to value. Takes an hour but doesn't require an hour of thinking. The time is in the doing, not the deciding.

High-frequency. Happens often enough that the investment in automation pays back quickly.

Bad automation candidates:

- Work that genuinely requires judgment each time

- One-off tasks that won't repeat

- Tasks where the process itself generates insight (sometimes doing research manually reveals things automation would miss)

- Anything where the cost of errors is very high

What Can PMs Actually Automate With AI Tools?

The list of what PMs can automate has expanded dramatically in the past two years. Here's what I actually run on a regular basis.

Specific workflows I've automated

SEO content workflows. When we publish a new landing page, a workflow automatically enriches it with keyword data from our SEO tools, drafts initial meta descriptions, and flags optimization opportunities. What used to take our team hours of manual checking happens in the background while we focus on other things.

Blog reoptimization pipeline. Every week, a workflow pulls underperforming blog posts (based on traffic and ranking data), analyzes what's ranking above us for those keywords, and generates specific recommendations for improvement. I review and prioritize; the system does the research.

Competitor monitoring. Daily automated scrapes of competitor pages flag meaningful changes—new features, pricing updates, messaging shifts. No more "we should check what X is doing" in meetings. I already know, because I got a summary that morning.

Localization pipeline. Content goes in, translated and localized versions come out, formatted for our CMS. We went from manually managing translations for each page to auto-generating pages in 40+ languages. The time savings are measured in days per month.

Meeting prep summaries. Before certain recurring meetings, a workflow pulls relevant metrics, compares them to previous periods, and drafts a narrative summary. I edit and add insight rather than starting from scratch.

Research synthesis. When I need to understand a topic quickly, I can run a workflow that pulls relevant sources, summarizes key points, and organizes findings by theme. Not perfect, but a better starting point than a blank page.

Reporting drafts. Weekly growth updates, monthly reviews, quarterly planning inputs—all start as automated drafts based on our data sources. I spend my time on insight and narrative, not on pulling numbers and formatting tables.

What tools do you need to get started?

The core stack I use:

ToolPurposeLearning Curven8nWorkflow automation platformMedium (weekend to learn basics)Claude/ChatGPT APIAI processing within workflowsLow (if you can prompt, you can use it)Airtable/Google SheetsData storage and manipulationLowZapierSimple automations and integrationsVery lowMake (Integromat)Alternative to n8n, more visualLow-Medium

You don't need all of these. Start with what you have access to. Claude or ChatGPT alone, used intentionally, can automate significant cognitive work. Add n8n or Zapier when you need scheduled runs and integrations.

The specific tools matter less than building the habit of asking: "Is this something I should automate instead of doing manually?"

Why Isn't This Engineering's Job?

I could file tickets for all of these automations and ask engineering to build them. They never would—and they shouldn't.

Why should PMs build their own automations?

Engineering has higher-leverage work to do. Every hour an engineer spends building a PM productivity tool is an hour not spent on the product. My automation needs aren't more important than user-facing features.

PM workflows require PM context. The automations I build are specific to how I work, what data sources I use, and what outputs I need. An engineer building to my spec would need constant clarification. It's faster to build myself.

Workflows change frequently. My needs evolve as priorities shift. An automation that's useful this quarter might be irrelevant next quarter. I can iterate on my own workflows instantly; engineering tickets have lead times.

Building teaches you what's possible. When I evaluate product decisions, I have informed intuition about what can be automated vs. what genuinely needs human work. That intuition comes from building, not from reading about building.

What's the line between PM automation and engineering work?

PM-built automations should be:

- For your own productivity, not user-facing

- Low-stakes if they fail (wrong analysis is annoying; broken checkout is catastrophic)

- Acceptable at "good enough" quality (doesn't need to be production-grade)

- Easy to manually override (you can always do it by hand if the automation breaks)

Engineering should handle:

- Anything user-facing

- Anything with security or compliance implications

- Anything that needs to scale beyond your personal use

- Anything where errors have significant consequences

The heuristic: if it breaks and no one notices except me, I can build it. If it breaks and customers notice, engineering should build it.

How Do You Get Started Without Technical Skills?

The barrier to entry is lower than you think. You don't need to be a developer. You need to be willing to spend a few hours learning tools designed for non-developers.

How hard is it really to learn these tools?

n8n: I learned the basics in a weekend. The interface is visual—you drag nodes and connect them. The mental model is "trigger → process → action." If you can draw a flowchart of your workflow, you can build it in n8n. More complex workflows take longer, but you learn by building.

Zapier/Make: Even easier than n8n. More limited in what they can do, but the learning curve is nearly flat. If you can use a web app, you can use Zapier.

AI APIs (Claude, GPT): If you can write a prompt, you can use an AI API. The API just lets you send prompts programmatically instead of typing them into a chat interface. The complexity is in the prompting, not the integration.

The honest answer: you can build your first useful automation in an afternoon. You'll build better automations after a few weeks of practice. You'll build sophisticated workflows after a few months. The learning curve is real but not steep.

What's a good first automation to build?

Start with something that:

- You do at least weekly (enough repetition to justify the investment)

- Has a clear trigger (every Friday, when X happens, when Y is added)

- Has predictable steps (you could write down the process as a checklist)

- Would take 30-60 minutes to do manually (enough time savings to feel the benefit)

Examples of good first automations:

- Weekly metrics summary: Pull data from your analytics tool, format into a template, send to yourself or your team.

- Competitor alert: Monitor a competitor's website for changes, summarize what changed, send yourself a notification.

- Meeting notes processing: Take raw meeting notes, extract action items, format into your task manager.

- Content brief generation: Take a keyword or topic, pull research from relevant sources, output a structured brief.

Start simple. Get something working. Then expand.

What's Different About PM Productivity in 2025?

The fundamental job of a PM hasn't changed: understand users, prioritize problems, ship solutions, measure impact. But the tools available to do that job have transformed.

How has AI changed what PMs can do alone?

Research that used to take days takes hours. Competitive analysis, market research, user interview synthesis—AI can accelerate all of it. You still need judgment to interpret, but gathering and organizing information is dramatically faster.

Writing has a starting point. First drafts of specs, documentation, communications—AI gets you 60-80% of the way there. Your job shifts from writing to editing.

Analysis is accessible without SQL. You can describe what you want to know, and AI can help you get it from your data. Not a replacement for proper analytics engineering, but a huge accelerator for ad-hoc questions.

Prototyping happens before engineering. Mockups, workflows, even simple functional prototypes—PMs can build and test ideas before consuming engineering resources.

Personalization scales. Communications, stakeholder updates, even product recommendations—AI makes it feasible to tailor at scale.

The net effect: the range of what a single PM can accomplish has expanded significantly. The question is whether you're taking advantage of that range.

What new expectations come with these capabilities?

Here's the uncomfortable part: if AI makes PMs more productive, organizations will expect more productivity. The bar is rising.

A PM in 2020 who spent half their time on research, writing, and coordination was normal. A PM in 2025 who spends half their time on work AI could accelerate will seem inefficient.

This isn't about working harder. It's about working differently. The PMs who thrive will be the ones who:

- Identify which of their tasks AI can accelerate and actually use AI for them

- Build systems instead of doing tasks so the acceleration compounds

- Focus their human effort on judgment, relationships, and creativity—the parts AI genuinely can't replace

The risk of not adapting isn't just personal inefficiency. It's becoming less valuable relative to peers who have adapted.

How Does Staying Hands-On Make You a Better PM?

Beyond pure productivity gains, building your own automations improves how you do your job in less obvious ways.

What do you learn by building yourself?

You understand what's actually possible. The most common PM failure mode is proposing solutions that are technically feasible but impractical—too expensive, too complex, too fragile. Building automations gives you calibrated intuition about what's easy vs. hard in software.

You see the details that matter. When you build something yourself, you encounter edge cases, failure modes, and design decisions that you'd miss if you just wrote a spec. That detail-level understanding makes you better at specifying what others should build.

You learn to decompose problems. Automation forces you to break fuzzy goals into concrete steps. That skill transfers directly to product work: turning vague user needs into specific features requires the same decomposition ability.

You become more self-sufficient. The less you depend on other people to get things done, the faster you can move. Not because collaboration is bad, but because blocking on others is expensive.

How does this affect your judgment and credibility?

Your estimates improve. When you've built things yourself, you have better intuition for how long things take. You stop saying "that should be easy" about things that aren't easy.

Engineers trust you more. Engineers respect PMs who understand what they do. Demonstrating that you can build—even simple things—changes how you're perceived. You're not just someone who asks for things; you're someone who gets it.

You ask better questions. Understanding how systems work lets you ask questions that get to the heart of technical decisions rather than surface-level questions that waste everyone's time.

You have backup options. When engineering capacity is constrained, you can prototype, validate, and in some cases solve problems yourself rather than waiting. That optionality is valuable.

What Are the Risks and Limitations?

Building your own automations isn't all upside. There are real risks and situations where it's the wrong approach.

When does building your own automation go wrong?

You spend more time automating than you'd spend doing. The classic trap. Before automating, estimate: how long will this take to build? How much time will it save? Over what period? If the math doesn't work, do it manually.

You build something fragile that breaks constantly. Bad automations create new work: debugging, fixing, maintaining. If you're spending more time keeping your automation running than it saves, you've made things worse.

You avoid the real problem. Sometimes "I should automate this" is procrastination dressed as productivity. If the underlying process is broken, automating it just makes broken faster.

You neglect the work that actually needs you. Building automations is fun. It's more satisfying than some of the messy human work of product management. Don't use automation-building as an escape from harder work.

You create technical debt for yourself. Automations accumulate. Each one needs occasional maintenance. At some point, managing your automations becomes its own burden. Be intentional about what you build and be willing to delete things that aren't worth maintaining.

What should PMs NOT try to automate?

Relationship work. Stakeholder management, team dynamics, user conversations—anything where the human connection is the point. AI can help you prepare, but it can't replace you.

Judgment calls. Prioritization decisions, strategic choices, product direction. AI can provide analysis, but the decision needs to be yours.

Anything where errors are costly. User-facing communications, legal/compliance content, anything with financial implications. Human review should be the last step for high-stakes outputs.

Learning opportunities. Sometimes the manual work teaches you something. The first time you do competitive analysis, do it yourself—you'll notice things automation would miss. Automate after you understand the work.

Novel problems. Automation works for repeated patterns. One-off challenges need human thinking.

Key Takeaways

- The expectation that senior PMs stop hands-on work made sense when leverage came only from coordinating humans—it makes less sense when AI tools multiply individual impact

- The real PM bottleneck isn't time management—it's repetitive cognitive work that requires your context but not your judgment

- Automate work that's repetitive, context-dependent but not judgment-dependent, time-consuming relative to value, and high-frequency

- PMs should build their own automations because engineering has higher-leverage work, PM workflows need PM context, and building teaches you what's possible

- Learning tools like n8n or Zapier takes a weekend; building your first useful automation takes an afternoon

- AI has raised the bar for PM productivity—the question isn't whether to adapt, but how quickly

- Staying hands-on improves your estimates, earns engineering trust, and gives you backup options when resources are constrained

- Risks include over-investing in automation, building fragile systems, and using automation-building to avoid harder work

FAQ

How much time do you actually spend on automation vs. product work?

About 2-4 hours per week on average, though it varies. Some weeks I build something new (more time); most weeks I'm just maintaining and tweaking existing workflows (less time). This investment returns roughly 10-15 hours of time savings per week on work I'd otherwise do manually. The ROI is significant, but you do have to invest upfront.

What if my company doesn't allow tools like n8n or external AI APIs?

Start with what you have. If you have access to ChatGPT or Claude, you can still automate cognitive work—just manually rather than programmatically. If you have access to Excel or Google Sheets, you can automate data processing. If you have access to internal tools with APIs, you might be able to build on those. The principles apply regardless of specific tools.

Does this replace the need for data analysts or other specialists?

No. My automations handle the routine stuff so specialists can focus on complex analysis. I'm not doing sophisticated statistical work or building production dashboards. I'm generating first drafts, pulling quick data views, and automating repetitive research. The specialists do the hard stuff; I automate the tedious stuff.

How do you know if an AI output is good enough to use?

Review everything before it goes anywhere. AI outputs are drafts, not finished products. For internal use (my own analysis, meeting prep, research), I scan for obvious errors and move on. For anything external (communications, deliverables), I edit thoroughly. The time savings come from not starting from scratch, not from skipping review entirely.

What's your advice for PMs who are skeptical about AI tools?

Try it for two weeks on one specific task. Pick something you do regularly that takes significant time—weekly reporting, research synthesis, competitive analysis. Use AI to help with just that one thing. After two weeks, decide if it's worth continuing. Most skeptics I've talked to who actually try become converts. The tools are better than you think, and improving rapidly.

.png)

.png)

.png)